Across diverse religious practices, cultures, and economic philosophies, the act of giving has been cherished as a virtuous endeavor that enriches both the giver and the recipient. From a religious perspective, the giver (who is blessed with prosperity) bears a responsibility to care for the receiver, recognizing that their prosperity is the result of the joint efforts of all human beings. Consumerism and materialism too in their defining spirits incorporate giving and sharing as these always render a feeling of contentment which is sought by them.

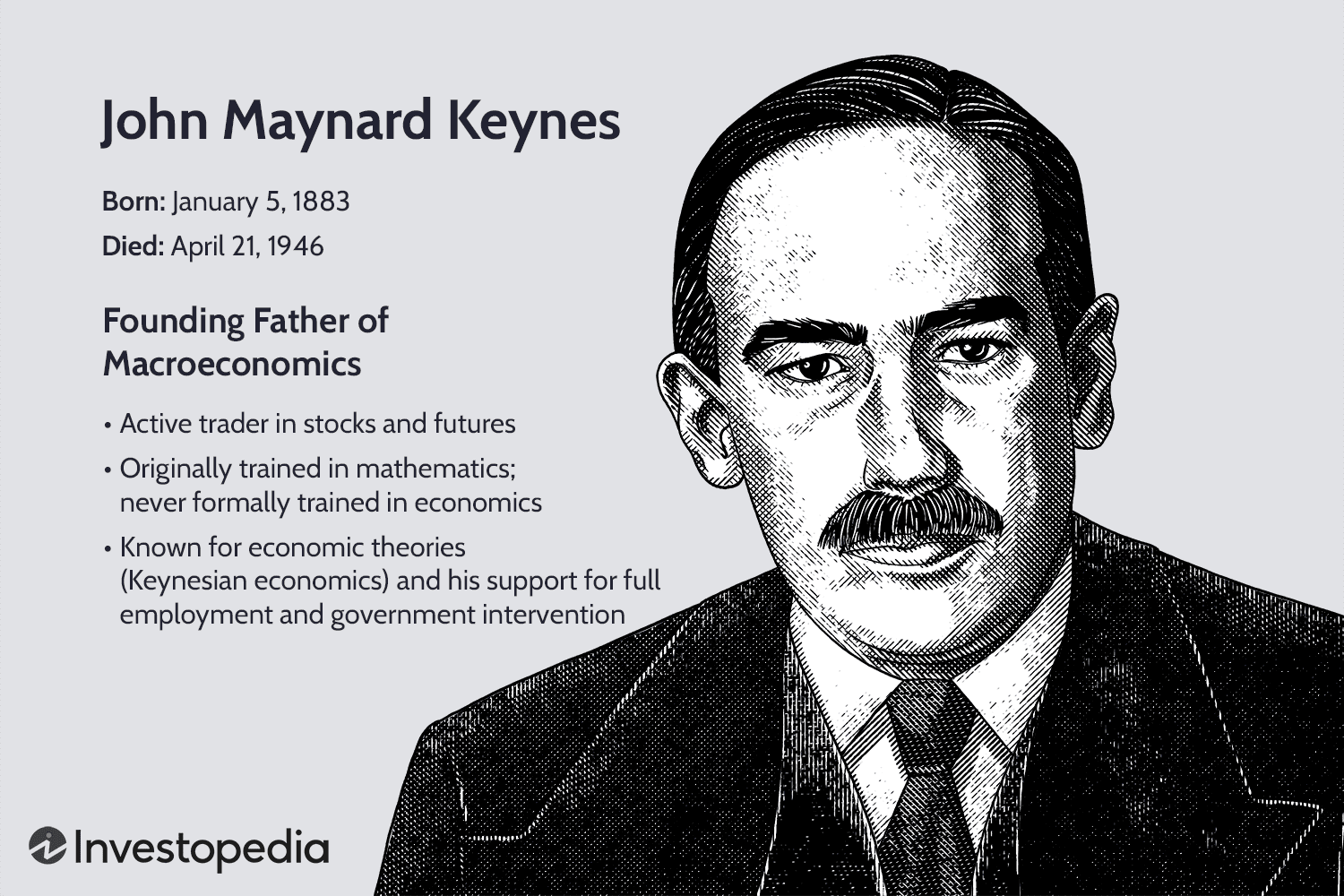

This article delves into the profound concept of generosity, drawing examples from various religions and economists that uphold the timeless value of charity. Effective demand as expounded by the renowned economist John Maynard Keynes continues to resonate within the realm of economists and influencing governments worldwide in their policy-making initiatives, in its essence, carries the need to transfer purchasing power from rich pockets to poor ones.

All religions around the world encourage the acts of spending for the betterment of humanity through charity, alms, and extending help to those in need. Moreover, this practice is viewed as a fundamental cornerstone for spiritual growth and the well-being of communities. According to religious teachings, aiding others takes precedence over self-benefit.

In Christianity, the parable of the Good Samaritan (a helpful or generous person) serves as a prime example of aiding those in need, transcending social and religious barriers. The teachings of Jesus emphasize selflessness and the significance of giving for the collective good. This message is particularly evident in the New Testament. In Christianity, all believers are united sharing everything in common. Possessions were sold out by the Apostles to support those in need.

Similarly, in Buddhism, the concept of “Dana” underscores the importance of giving without expecting reciprocation. This practice is believed to nurture compassion and reduce attachment to material possessions. In Hinduism, “dana” holds a pivotal role in dharma (righteousness) and is viewed as a means of purifying the soul and fostering a harmonious society. Islam too places a significant emphasis on the concept of spending and disgraces stinginess. In al-Quran, the term ‘انفاق’ (infaq- spending) is frequently mentioned, with its derivatives appearing nearly more than seventy-three times. There are other verbs in the Quran that also convey the meaning of ‘انفاق’. These noble verses encourage believers to utilize their wealth for the betterment of one’s own self as well as fellow human beings. In Islam, giving is viewed as a manifestation of gratitude towards Allah and a means to cleanse one’s soul.

Upon closer examination of the Quran, it becomes evident that the concept of ‘انفاق’ surpasses that of ‘الكسب’ (earnings) in both frequency and emphasis. The Quran advocates for various forms of spending, including obligatory almsgiving (Zakat), voluntary charity (Sadaqah), and acts of benevolence. The repeated mentioning of ‘انفاق’ underscores the profound importance of selfless giving as a means to nurture social equality and compassion. A crucial aspect of the obligation of Zakat is that if every individual fulfills their Zakat duty according to the principles of Sharia, then no one would remain in poverty and the financial harmony will prevail.

Expenditure, and its importance

Transitioning from religious teachings to economic philosophy, the insights of British economist John Maynard Keynes offers a unique perspective on the importance of expenditure. Keynesian economics, developed during the aftermath of the Great Depression, emphasizes the role of government intervention to maintain economic stability.

Keynes argued that during times of economic downturn, increased government spending could stimulate demand and boost economic activity. This idea, known as fiscal stimulus, was instrumental in overcoming the challenges posed by the Great Depression of the 1930s. Keynesian economics posits that by putting money in the hands of consumers, governments can stimulate spending, drive production, and ultimately prevent or alleviate economic recessions. Resources not put into circulation often necessitate government intervention, particularly during unforeseen circumstances like depression or unbearable unemployment. Such governmental intervention while accompanied by willing contributions from individuals blessed with wealth might enhance its effects multiple times.

Expressing in the present-day context, as per Keynes, effective aggregate demand needs to be enough to generate full employment in an economy. In the classical economic model, as per ‘Say’s market law’, supply generates its own demand. This proved wrong during the market upheavals of the 1930s. it was the Second World War which generated effective demand and that was due to governmental expenditure. Keynes was the finance minister of Britain during the Second World War. Keynes noted that while individual savings may be prudent, if everyone saves it may lead to reduced demand, lower production, and prolonged recession. He further observed that individuals hold cash for transaction purposes and as a buffer against uncertainty. This is particularly true when interest rates are low.

Hence, lower effective aggregate demand and greater aggregate supply is always a possibility. Keynes propounded the concept of multiplier effect: A concept explaining how an initial change in spending results in a larger change in overall economic activity. It reflects the chain reaction of increased spending, income, and demand.

One key takeaway from Keynesian economics in the relevant context is the significance of keeping money flowing within the economy rather than hoarding it. Releasing money into the market can lead to a ‘multiplier effect,’ resulting in manifold positive impacts.

Understanding People’s Tendency When it Comes to Expenditure:

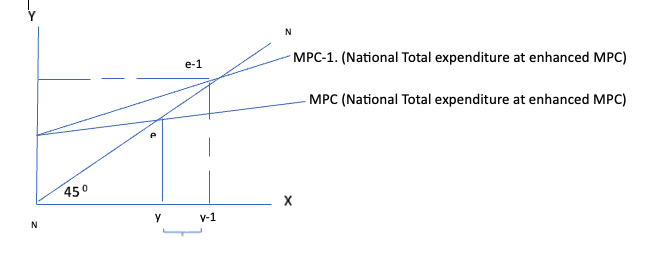

In the Keynesian ‘multiplier effect’ model, people’s spending habits are considered as a constant. When individuals receive extra income, they tend to spend a particular portion of it. Keynes termed this tendency as the ‘Marginal Propensity to Consume‘ (MPC). The lower the MPC, the smaller the multiplier effect. This means that if people spend a lower proportion of their extra income, there will be lower demand, lower employment, and a lower increase in income. The Keynesian macro-economic model illustrates this phenomenon in a famous diagram.

In this diagram, 450 Normal represents incomes equal expenditures. In classical economics, it is believed that an economy naturally reaches this normal state through market mechanisms. As per this norm, the current Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC) in the diagram keeps the economy at point ‘e,’ resulting in a National Income of ‘y.’

Keynes proposed that through government intervention if aggregate demand can be increased from its existing MPC to MPC-1 by inducing additional expenditure ‘a,’ the economy would eventually settle at point ‘e-1,’ resulting in a National Income of ‘y-1.’ The increase in income is represented by ‘b,’ multiple times ‘a.’ Many successful government policies are based on this notion of multiplier effect.

Managing Economic Crises through Religious Admonition

Returning to religious teachings, if mankind can increase the Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC) by a moderate amount, the results could be even more promising. This can be explained through the following diagram. Instead of induced expenditure by governmental agencies, an enhanced MPC through religious admonition would lead to a greater increase in National Income.

Since our textbooks, being secular, cannot directly suggest religious teachings, this concept has been referred to as the ‘Nudge Theory.’ Whether it’s through religious admonition or working of the Nudge Theory, the issue of unemployment can be addressed through this process, and all this can be achieved without the risk of inflation.

Excellent. Let our economics text books include the last diagramme of your article.

This commendable task’s credit goes to your inference from markets working mechanism.